By Marilyn Mehlmann

This article is derived partly from the book Empowerment – A Guide for Facilitators and partly from the workshops on ‘Values, Empowerment and Transformation’ held 14-15 July, 2023 at Ydrefors, Sweden. It looks briefly at the nature of transformative learning and its relation to empowerment; and at the role of the facilitator or educator in enabling transformative learning.

What is empowerment?

We are all hypnotised, said Willis Harman on the subject of perceptions. Hypnotised into believing we are less than we are, into staring at what is – or may be – impossible. “Perhaps the only limits to the human mind are those we believe in.”

Empowerment is a necessary component of (positive) transformative learning. As educators and facilitators of personal development, we can plan a program of empowerment with a high likelihood of success (see below, Empowerment Spiral).

That does not, however, mean that we can plan for an outcome to include transformative learning, which follows its own logic and internal timetable.

Becoming who we are

The process of empowerment is, at its core, about becoming (Ferrucci): becoming increasingly comfortable in one’s own life, in the feeling that ‘I am good enough just as I am’. It is thus in the first place the inner journey of an individual, a group or a community.

Empowerment can take place slowly or swiftly: in tiny steps, or in breath-taking transformation. For some, it might happen over the course of years as they develop their own voice and gradually enlarge their field of influence, for others it might be a sudden shift of perspective, an ‘Aha’ moment, that breaks their shackles and unleashes their voice.

From surviving to thriving

Many people and groups are stuck in a belief that change – if it comes at all – comes from an outside source, and that little change, or no positive change, can be expected. In such a situation, with little or no hope, there is no energy for change; the best that can be hoped for is no-change, or mere survival.

“When an inner situation is not made conscious,

– Carl Jung

it happens outside, as fate.”

And in just such a situation, even a very small, observable change can cascade into multiple small changes, with a growing feeling of wonder and willingness to experiment. Indeed, it’s not even necessary for the early attempts to be successful. The mere act of taking an initiative and seeing results can be empowering, also if the results themselves are not what was hoped for.

Initial changes can be quite modest, sometimes even recommended as ‘the smallest change that will make a difference’, which is indeed good advice for climbing out of survival mode.

The nature of personal transformation

Unlike ‘ordinary’ change, transformation cannot be planned or managed. It takes place when conditions are right, including the preparedness of the individual or group. No doubt all long-term facilitators share this experience:

At a conference, a man who looked familiar greeted me eagerly, saying ‘Thank you SO much – your workshop changed my life!’ When was that, I asked cautiously. ‘It was 17 years ago – you remember! It took a few years but then I realised…’

The ways of transformation are indeed unpredictable.

Change and plans

When we initiate a change process, it’s normal and indeed essential to have an idea of potential outcomes, and to use them as a basis for planning. For instance, an empowerment program is intended to enhance the action competence of each participant, and that might include specific outcomes like mastering a new language or acquiring a new skill.

However, once the process has begun, the plans are of marginal use. Transformative change – say many oracles (eg Ziegler, Fritz) – is not really something you plan, it’s something that happens when conditions are right.

The growing edge of the comfort zone

Danaan Parry put the same thing differently (2009). He said that in the centre of our ‘comfort zone’ – where there are no dissatisfactions! – we have no incentive to change. If we are thrown too far outside of our comfort zone, presumably to a place where the challenges are too great for our hopes to handle, then we tend to ‘freeze’; also no change.

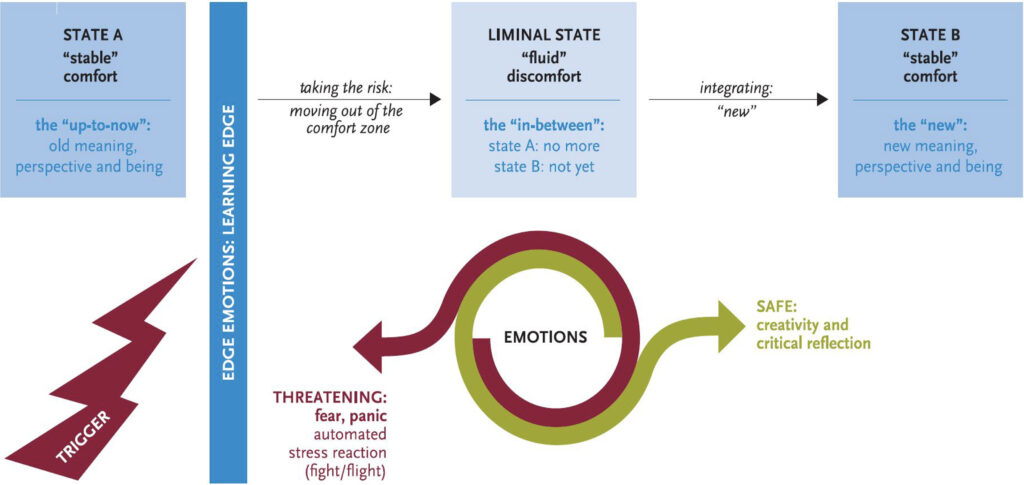

What we need, he said, is to propel ourselves, or our students/participants, to ‘the growing edge of the comfort zone’. This is where incentives to change can be found – and also where participants may experience ‘edge emotions’ such as those in the ‘fear zone’ (see the figure below) that can be challenging for the facilitator.

| A personal experience of transformative learning Way back in the 1980s we were attracted to the idea of an ecovillage: a community where we would explore, together with others, how we might ‘live more lightly on the earth’. But our efforts to move to, or build, an ecovillage were dogged by failure. Then one evening at a workshop on sustainable lifestyle, the realisation struck: we don’t have to move house in order to take action. We can ‘live more lightly’ here and now! From ‘failed ecovillager’ to ‘conscious lifestyler’ was a tectonic shift! |

Edge emotions

Leaving the comfort zone can trigger both positive and negative edge emotions, corresponding to hope and disappointment, or curiosity and fear:

The role of the educator

To be fully effective, an empowerment program needs to create conditions for both ordinary, often incremental change, and for transformative learning. The facilitator needs to be sufficiently responsive to recognize signals of preparedness, and sufficiently agile to accommodate different needs within a group. As both Eisenhower and Churchill are reputed to have said: plans are worthless, but planning is everything.

Program design

A conventional process to influence behaviour (including improving action competence) starts with information:

It all seems very logical. But we also know very well that it’s a poor model of reality. We inform and inform, but the desired changes fail to materialise.

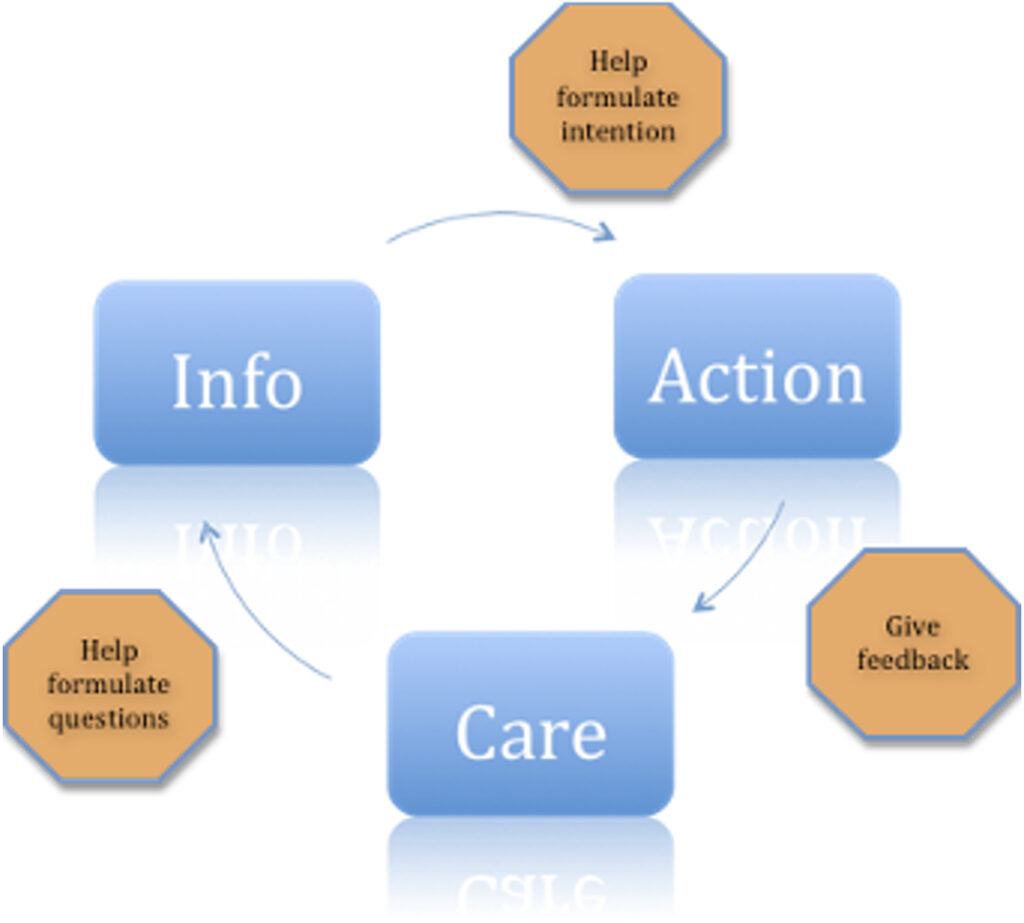

A better model, based on multitudes of observations of what happens when people do, in fact, change their habitual behaviour, is that of a circle:

This circle—which, through repetition may become a positive empowerment spiral—offers the educator far more options than simply transferring knowledge. Indeed the most powerful entry point for an intervention is, counter-intuitively, at the point of Action: an invitation to experiment can be the quickest route to new insights and changed behaviour.

However, the necessary basis is caring. Only by experiencing and expressing care for both the topic and the participants can an educator create a sufficiently safe and trustful space for transformative learning to take place

Images of the future

Once trust is established, an important focus for the facilitator is to create good conditions for consciously chosen change. This inevitably includes working with the participants’ conscious and unconscious images of the future. In addition to hopes and fears, we can work with their expectations concerning the future.

• If what I fear is also what I expect to happen, then I have every reason to work for change – though I may feel overwhelmed by the challenge.

• If what I hope for is what I expect to happen anyway, I have no reason to work for change: I need only wait, and everything will be perfect.

“Change happens when there is a reasonable balance between dissatisfaction and hope.”

– Warren Ziegler

In some cultures, and with some individuals, one or the other is conspicuously lacking. Given the mass-media culture of today, there is frequently a bias towards dissatisfaction and indeed fears.

Is it possible that a combination of small hopes and small dissatisfactions is a basis for small changes? Whereas a combination of large hopes and large dissatisfactions can give rise to major changes? If that is the case then we might expect that—absent ‘sudden’ events—transform-ative change would be most likely to take place when both hopes and dissatisfactions are high. For more on this, see Biester & Mehlmann

SKILLS TO TEACH

Empowerment and transformative learning are generally positive for both the individual and the community. However, when inappropriately applied, such programs can occasionally enable or facilitate undesirable behaviour, from denying responsibility to manipulation and oppression. The key difference is in attention to ethics.

Ethics and values

Doubtless every major spiritual tradition or movement has a set of ethical principles: guidelines for how to live a good or righteous life. One example is that of the Essenes, taken from the Dead Sea scrolls (Pettitt & Mehlmann). It’s particularly interesting because it places heavy emphasis on the value of relationships: with oneself, with other people, and with all other beings. Relationships are also shown in most modern surveys to be the key to health, wellbeing, and longevity (Evans).

“Much of wisdom is expressed in how people interact with and treat one another.”

– Louis Cozolino

Deep Listening

A key to developing positive, caring, long-term relationships is the ability to listen deeply—first to oneself, then also to other people.

A method for practising and teaching Deep Listening is documented in the Hosting Transformation Toolbox. The method was developed by Warren Ziegler based, he said, on Daoist praxis. The basis is an ability to ‘park’ thoughts, feelings, influences, to create inner silence, and to hold a non-judgmental position.

Ziegler said that when you deep-listen to yourself, you are ‘listening to the voice of your spirit’. And indeed it has much in common with meditation, and even with prayer.

Empowering meetings

Whenever we bring people together, whether the setting is a classroom, a business meeting, or a community gathering, there is a risk of falling back into outmoded forms of organisation, where some people are more important than others. The leader who clings to control of the agenda, and to being ‘the one with the answers’, is not enabling transformative learning.

This is not to say that a teacher or other group leader does not have a special position. Indeed they—we—do: but it is one of responsibility rather than privilege. In addition to being a questioner and a source of information, the responsibility is to foster open, trustful, non-judgemental communication within the group, and to ensure (if at all possible) that the session or meeting is brought to a satisfactory conclusion.

The Hosting Trans-formation Toolbox contains methods for conducting meetings, for instance the Synergy method, and for reaching mutually acceptable decisions. See also Biester & Mehlmann.

From the personal to the planetary

To enter fully into the work of enabling transformative learning, we need to embrace the insight that each one of us carries within us the resources we need in order to ‘become more fully ourselves’ and to exert greater influence in our personal lives (Ferrucci; Rogers).

And, we live in an era of escalating global and local crises. “To navigate these troubled waters with a sense of joyful participation, each person needs not only a strong sense of self but also a desire and ability to collaborate: to become an active member of his or her community or communities. Individual wellbeing cannot be separated from the wellbeing of the community.” (Wahl).

Every step we, as educators and facilitators, can take to enable transformative learning helps to counteract those escalating crises. Our work affects not only our students or participants, but indeed the whole planet.

Competence Factors

From Biester & Mehlmann (2020)

Knowledge

Knowledge includes the cognitive knowledge and understanding of how the world (reality) is configured and functions, of the (scientific) processes and mechanisms that operate in this reality, and of the place, position and degrees of freedom that individuals, groups, organisations and society can have in this reality.

Includes cognitive and intellectual tools (e.g. critical thinking) for acquiring and developing the knowledge and understanding.

Skills

Skills refer to the practical and manual, emotional and intellectual skills for managing, manipulating and modifying physical and social reality, from the simplest to the most complex conditions. They are related to day-to-day tasks and survival (e.g. writing with a pen, self-discipline, showing empathy), to professional performance (e.g. in education, engineering, agriculture or coding), to scientific analysis, and to meeting a variety of challenges (e.g. establishing trust, reducing CO2 emissions or finding a cure for cancer).

Attitudes

Attitudes cover the social-psychological ‘states’ or ‘orientations’ of an individual or group. They refer to the manners, dispositions, feelings and position regarding a person, group, entity, condition, situation or task. An attitude can be held in a more or less conscious manner. Attitudes can influence behaviour and performance. They provide (part of) the argumentation for behaving in a certain way. But behaviour and performance can also shape attitudes: they become the justification for behaviour. ‘Attitude’ is often used to describe a ‘tendency’ or ‘orientation’, especially of the mind. Therefore, ‘attitude’ is often equated with ‘mindset’ or even ‘perspective’.

Aptitude

A person’s aptitude is their innate or acquired ability to do something, to undertake action and to make effective use of knowledge and skills. When ‘aptitude’ is equated with ‘talent’ it is seen as an innate characteristic (e.g. an aptitude or special talent for mathematics). However, through experience and practice aptitude can also be acquired. More generally, aptitude can denote a readiness or quickness in learning; which is usually seen as a sign of intelligence.

Disposition

Disposition is closely related to attitude, but it also overlaps with aptitude. It is the predominant or prevailing tendency of one‘s spirits. It is an individual’s ‘natural’ mental state and emotional outlook or mood. Disposition can be seen as a state of mind regarding something or an inclination towards a certain form of action or behaviour (e.g. a disposition to do good; a disposition to take risks).

Approaches to Expanding Competences

By Clinton Callahan, in A Transformative Edge - Knowledge, Inspiration and Experiences for Educators of Adults, U. Biester & M. Mehlmann (eds), Transformation Hosts Int’l. Publ. (2020), pp 16-17.

1: BRIGHT FUTURE NOW

In the midst of the world’s upheavals, many people are looking for a more positive and effective way forward – for themselves and for the world. The Bright Future programme, including the seven-week Bright Future Now online course and the worldwide Bright Future Network, provides such a whole-system transformational pathway.

This programme was developed by Dr Robert Gilman, former astrophysicist and long-time sustainability thought-leader. It provides the frameworks, skills, experiences and community to start living your own bright future and to become a potent seed-point for the emergence of the world’s bright future.

At its heart, the Bright Future programme is a pathway to expanding personal capacity to make positive change at all levels and to spend more time living in the deep strengths of love and creativity. Robert Gilman writes:

“We’ve found this particularly good for people who are:

- More interested in building the new culture than fighting the old

- Ready to combine personal, interpersonal and project-oriented skill-building and growth

- Interested in connecting and collaborating with others from all kinds of backgrounds who also look toward the future with a sense of possibilities.

Because the work is so foundational, it works well for a wide variety of people.

2: POSSIBILITY MANAGEMENT

Since the 1970s, a committed and growing community has been working to bring to life an ever-evolving collection of practices and perspectives called Possibility Management. In Possibility Management, our ways of relating to thinking, feeling and doing are transformed; this is a process we call ‘upgrading human thoughtware’.

With new thoughtware, you can create completely new life results without changing the circumstances. This unleashes huge human potential. Realizing this potential was what, in 1975, set me on a development path that has unfolded into the global, ever-evolving community of practice now called Possibility Management.

At its core are the twin assertions: “What is, is,” and “Something completely different from this is possible right now.”

What it is

Possibility Management builds bridges between modern culture (which brings humanity to its limits) and next cultures (which are regenerative and sane). It offers modern initiation into adulthood. We create safe and beautiful training spaces to explore richly exciting territories of experiential learning.

Today Possibility Management is a global gameworld of 42 Trainers plus Possibility Coaches, Possibility Mediators, Possibility Psychologists and Possibility Team Spaceholders

All Possibility Management material is copylefted, meaning it cannot be copyrighted. The entire work of Possibility Management is ‘open-code thoughtware’, created from an endless resource and dedicated to the Creative Commons for the benefit of everyone.

- Possibility Management is used in numerous applications, such as:

- Transformational personal development

- Initiations into adulthood and archetypal domains

- Emotional healing processes

- Relationship skills

- Communication, conflict resolution, and decision-making processes for circular meetings

- Remembering how to live without the crutches of modern technology

Possibility Management is context-centred. Its context begins with radical responsibility. The point at which a culture takes responsibility can be easily determined. For example, if you ask the question, “When a small child makes a mess, who cleans it up?” the obvious answer is, “The parents.” Modern culture is making huge unconscionable messes with no intention of ever cleaning them up. Modern culture is firmly centred on child-level responsibility. Where are the adults? Adults are made by other adults.

Every project, every community, every company, every culture, every government, every religion makes a choice about the context out of which their rules of engagement and traditional practices emerge. That context determines to what degree responsibility is made conscious, which awareness forms the basis of interactions with children, women, men, with animals, with economics, with materials, with Gaia. It is possible to assess existing choices and make new conscious choices immediately, even if you have been following your current unconscious choices for decades.

References

U. Biester & M. Mehlmann (eds) (2021), A Transformative Edge, Hosting Transformation Library, Berlin

L. Cozolino (2018), Timeless: Nature’s Formula for Health and Longevity, W W Norton & Co., New York

K. Evans (2018), ‘Why Relationships Are the Key to Longevity’, mindful.org, 17 September 2018

P. Ferrucci (1982), What We May Be: Techniques for Psychological and Spiritual Growth Through Psychosynthesis. J.P. Tarcher, LA

R. Fritz (1999), The Path of Least Resistance – Learning to Become the Creative Force in Your Own Life. Fawcett Publications, MN

D. Gershon & G. Straub (2011), Empowerment: The Art of Creating Your Life as You Want It, Sterling Publishing Co. Inc., New York

W. Harmann (1998), Global Mind Change: The Promise of the 21st Century. Sausalito, CA; Berret-Koehler Publishers. Internet Archive, archive.org/details/ globalmindchange00harm.

Hosting Transformation Toolbox, Visionautik Akademie, Berlin hostingtransformation.eu/toolbox/

C.G. Jung (1991), Aion: Researches into the Phenomenology of the Self, Routledge, London

M. Mehlmann (2019), ‘An Empowerment Spiral’ (unpublished manuscript) docs.google.com/document/d/1Si7b66Im-qIh1RhbWp_ZNyxlsIqmaMYgPQaHenn9CqI

M. Mehlmann (2023), Empowerment: a Guide for Facilitators, Hosting Transformation Library, Berlin

M. Mehlmann & O. Pometun (2013), ESD Dialogues: Practical approaches to Education for Sustainable Development, Books on Demand, Norderstedt, Germany

K. Mälkki & L. Green. (2014), ‘Navigational Aids: The phenomenology of transformative learning’. Journal of Transformative Education 12.

D. Parry (2009), Warriors of the Heart. 6th Printing edition, BookSurge Publishing

G. Pettitt & M. Mehlmann (1997), ‘Essene Principles for Right Living’ (unpublished manuscript) docs.google.com/document/d/1JgHao-unr_sZhfNg1sjpfP0f7TdcIcZobfFWfld80Fs/

C. Rogers (1995), Way of Being. Houghton Mifflin Co., Boston/New York.

D.C. Wahl (2016), Designing Regenerative Cultures. Triarchy Press, Bridport, UK

W. Ziegler (1995), Ways of Enspiriting: Transformative Practices for the Twenty-First Century. Fia International, CO

W. Ziegler (2002) When Your Spirit Calls – in Search of Your Spiritual Archetype. Fia International, CO.

Published in Neohumanist Review, Issue 2, March 2024, pp 70-77.